Risk may still be low, but findings lead scientists to call for better studies

Triatoma gerstaeckeri collected in Southeast Texas. Credit: Rodion Gorchakov

Every year, the hearts of millions of Central and South Americans are quietly damaged by parasites. During the night, insects called kissing bugs emerge by the hundreds from hiding places in peoples mud and stick homes to bite their sleeping victims. The bugs defecate near the punctured skin and wriggling wormlike parasites in this poop may enter the wound and head for their victims' hearts. There, in about a third of victims, they damage the organs for decades before causing potentially lethal heart disease. Around 12,000 people worldwide die each year from the ailment, called Chagas disease.

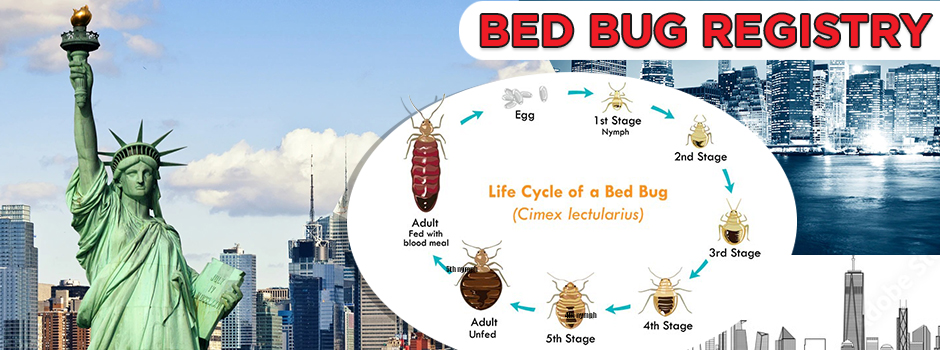

Scientists thought Americans were safe in their sturdier houses. Now some are not so sure. Chagas-infected kissing bugs do enter at least some southern U.S. dwellings and bite people living there, recent studies suggest. And a new study published two weeks ago raises the specter of Chagas from another more familiar insect pest: bed bugs, found all over the country. Biting bed bugs have been found to transmit the parasite between mice.

The bed bug effect has not been demonstrated yet among people but these studies have made some physicians and scientists wonder if they have underestimated the chance of acquiring Chagas in this country. We are very likely missing [Chagas] cases, said a May 2014 editorial in The American Journal of Medicine. A systemic survey of the high-risk population in the U.S. is urgently needed.

Thats a sentiment echoed by at least one CDC scientist. We know that people are acquiring this infection in the United States. But it's not common, says Susan Montgomery, epidemiology team lead of the Parasitic Diseases Branch at the CDC. Epidemiologists do know that eight million people in Central and South America and up to 300,000 U.S. immigrants are infected. Can we interpret that to say we know a lot about this? No, we don't know much. We really need more studies to understand what the risk is, Montgomery says.

Kissing bugs carrying Chagas are prevalent throughout the southern U.S. and 24 mammal species can act as reservoirs for the disease. Although it has long been known that kissing bugs carrying the Chagas parasite, which is called Trypanosoma. cruzi, conventional wisdom held that the bugs in the U.S. are repulsed by our well-sealed homes with solid walls and prefer to nest in animal burrows anyway. Until now only 23 cases of U.S.-acquired Chagas have been identified, the first recognized as early as 1955. But the flurry of new results hint the rarity of cases may have more to do with a lack of looking than a lack of disease. There's a long history of positive bugs in the southern United States, and a long history of mammals being infected, says Melissa Nolan Garcia, a research associate at Baylor College of Medicine's National School of Tropical Medicine who has studied southeastern Texas blood donors infected with T. cruzi. It's just that we're not doing enough to look at actual humans.

One actual human, a 74-year-old woman in rural New Orleans Parish, was found to have contracted Chagas from kissing bugs invading her home in 2006. The bugs had bitten her more than 50 times and left her walls and nightgown streaked with bug feces. Twenty dead bugs were found in her home and in an additional building on her property with a bed after fumigation and over half were infected with T. cruzi. Neither nymphs nor eggs were found in the house, indicating the bugs weren't even nesting there, but the home was 29 years old and had many gaps through which bugs could enter.

A year later, researchers collected an additional 49 kissing bugs from inside and around the outside of the womans home and found nearly half the bugs had fed on eight different humans. In the December 2014 issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases the scientists who made this discovery also reported that about 40 percent of all the bugs were infected with T. cruzi and three of the humans had been bitten by infected bugs. According to Garcia, those most likely at risk of contracting Chagas in the U.S. are outdoor enthusiasts in the South and Southwest, along with people living in substandard homes with many cracks and crevices permitting bug entry.

More evidence of human infection has emerged from studies of U.S. blood donors, whose donations have been tested for T. cruzi since 2007. In the last two years small studies have revealed that 7.5 percent of a national sample of Chagas-positive blood donors and 36 percent of a sample of donors from southeastern Texas seemed likely to have acquired their infections here in the U.S. Although blood donor samples may be biased in ways that make them poor representatives of the wider population, some researchers suggest blood donors may actually underrepresent infections: Poor or sick peoplethe most vulnerable to the parasitemay be less likely to donate.

More here:

Bed Bugs, Kissing Bugs Linked to Deadly Chagas Disease in U.S.

Residence

Residence  Location

Location