Yet, around this time began the re-emergence of a little insect pest, one thought long relegated to history, and since the start of 2000 it has become so common that in some parts of Australia it is almost impossible to find accommodation facilities without them. Unfortunately, this little insect has a preference for blood, with guests being the usual victim, and getting rid of this pest is both challenging and expensive. In fact, it is likely that the accommodation industry is losing tens to possibly hundreds of millions of dollars in combating this six legged blood sucker. Thus it appears that a millennium bug did arrive after all, although in this case, they are better known as Bed Bugs.

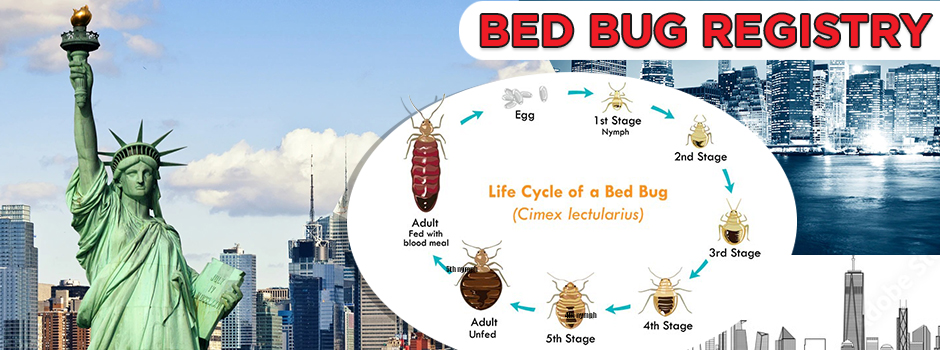

Bed bugs are insects and are related to the aphids and cicadas that appear in the garden; the difference being that bed bugs have developed a predilection for blood. The adult bed bug is around 5-6mm in length and up to almost 1cm when fully engorged with blood. They are flat and round in Bed Bugs: The Unwanted Guest body shape with deep dark red coloration, becoming almost black when full of blood.There are five juvenile stages, which range from 1-4mm depending on the stage and are cream in color when unfed.The development time of the lifecycle at 22oC is around two months, the adult female can lay up to 500 eggs throughout its life, and populations can become abundant in a short time.

Gale Brewer discusses the legislative process and the NYC Bed bug Menace from Kate Nocera on Vimeo.

Bed bugs, as their name implies, invade beds where they bite the sleeping victim.The bite can be painful and restless sleep often results. During biting, the bed bug injects saliva and this can cause various skin reactions such as the development of small indistinct red spots. Often these develop into large wheals, 2-5cm across, which are extremely itchy and very uncomfortable. In some cases hospitalization may be required if a severe allergic reaction develops, and the costs are usually borne at the expense of the facility. Fortunately, bed bugs do not transmit disease and often the most severe reaction relates to the mental trauma of being bitten. For many there is still a social stigma associated with bed bugs and people are often horrified and disgusted after being bitten, and claim to feel 'œdirty and unclean'. In such By STEPHEN DOGGETT circumstances it may become almost impossible to pacify upset guests and the Executive Housekeeper must demonstrate empathy in dealing with this challenging situation. Without a doubt, the greatest impact of bed bugs is that of the financial burden they impose on the accommodation industry. Guests bitten may refuse to pay the tariff and are not likely to return. Some resorts have even refunded whole holidays when guests have been severely attacked. Control is expensive and costs of $1,000 or more per room are not unheard of, especially in heavy infestations when multiple treatments and inspections will be required. During treatment, the affected room needs to be closed for a minimum of seven to ten days as the eggs will hatch (the insecticides do not kill the egg stage) and guests may be bitten during this period. There are reports of rooms being closed for two to six months in difficult to control infestations.The latest threat to the accommodation industry is that of litigation. One company in the United States was recently fined approximately AUS$500,000 after being found negligent when guests were badly bitten. Other court cases have followed and the hotelier rarely wins. As Australia is one of the most litigious countries in the world, it is just a matter of time before a facility is sued after a guest is attacked by bed bugs.

One Victims Story

The Horror of Bed Bugs and How to Effectively Treat them

Bed bugs become established in structures when they hitch a ride in boxes, baggage, furniture, bedding, laundry, and in and on clothing worn by people coming from infested sites. Poultry workers can carry bed bugs to their residences from their places of work. Bat bugs, poultry bugs, swallow bugs, and others are typically transported to new roosts by the principal host. An accurate identification of the bed bug species involved is essential to an effective control strategy. Many control failures can be traced to an incorrect identification. Bed Bugs Cimex lectularius L. Figure 1. Adult bed bug. Bed bugs hides in cracks, crevices, and seams during the day. They prefer narrow crevices with a rough surface where their legs and backs touch the opposing surfaces. Bed bugs cannot climb glass or smooth, plastic surfaces. Wood and paper surfaces are preferred to either stone, metal, or plaster; however, in the absence of preferred sites or during high population numbers, the latter will also be utilized. The aforementioned cracks and crevices should be filled with appropriate fillers, such as caulking.

The Horror of Bed Bugs and their eggs and how to kill them in your home. Safe and effectively from Rachel Mitchell on Vimeo.

Bugs will sometimes hide in the crevices of upholstered furniture and mattresses created by folds, buttons, and cording. Thoroughly vacuum all upholstery'”including the undersides'”mattresses, and pillows. Launder bedding and dry in a warm air dryer. Mattresses, upholstered furniture, and cushions can be treated with 'œdry' steam. It is best to use two professional-grade steamers with low vapor flow rates, each with one-gallon capacities. This allows one unit to always be hot between water refills. The steam should exit through a wand with multiple ports

Residence

Residence  Location

Location

Bed bugs cannot fly, they have been observed climbing a higher surface in order to then fall to a lower one, such as climbing a wall in order to fall onto a bed. The technique can also be used to help prevent bed bugs from crawling up along walls where warranted. Long strips of this taping method (i.e. curled duct tape over painter's tape) can be used on standard floors to cordon off, surround, and isolate infested furniture, to protect clean furniture, or as part of a treatment effort to help prevent bed bugs from crawling toward specific areas. Other common places to find bed bugs include: along and under the edge of wall-to-wall carpeting (especially behind beds and furniture).

Bed bugs cannot fly, they have been observed climbing a higher surface in order to then fall to a lower one, such as climbing a wall in order to fall onto a bed. The technique can also be used to help prevent bed bugs from crawling up along walls where warranted. Long strips of this taping method (i.e. curled duct tape over painter's tape) can be used on standard floors to cordon off, surround, and isolate infested furniture, to protect clean furniture, or as part of a treatment effort to help prevent bed bugs from crawling toward specific areas. Other common places to find bed bugs include: along and under the edge of wall-to-wall carpeting (especially behind beds and furniture).  Bed bugs like to hide in the cracks and electical outlets in walls, behind wallpaper, base boards and picture frames, between beds and around the creases of mattresses and in bedding materials. They have a rather pungent odor which is caused by an oil-like liquid they emit. Bed bugs are often carried into houses by clothes, luggage, furniture, and bedding. Or sometimes even by humans. Many household pests can be controlled or prevented by a simple insecticide bug spray on baseboards and exterior surfaces of the home. This is not the case when dealing with an infestation of bed bugs.

Bed bugs like to hide in the cracks and electical outlets in walls, behind wallpaper, base boards and picture frames, between beds and around the creases of mattresses and in bedding materials. They have a rather pungent odor which is caused by an oil-like liquid they emit. Bed bugs are often carried into houses by clothes, luggage, furniture, and bedding. Or sometimes even by humans. Many household pests can be controlled or prevented by a simple insecticide bug spray on baseboards and exterior surfaces of the home. This is not the case when dealing with an infestation of bed bugs. Bed bugs only search for blood donors when they are actually hungry. In the intervals between meals they spend their time in suitable hiding places in the vicinity of the bed. These may be crevices in the timber, joints in the bed, behind the headboard, beneath loose carpeting, behind pictures, behind wallpaper, in plug sockets, light switches, etc. When hungry, bed bugs come out from their retreat and start to search. Their senses are not capable of guiding them to a distant blood donor, but at distances of 5 - 10cm they will be attracted by the body warmth of the victim. Bed bugs can crawl up a wall and can also walk upside down on rough ceilings, but if they are not skilled they often fall down. This is the basis of stories that bed bugs, having observed that their victim had placed the legs of the bed in dishes of water, crawled up the wall and across the ceiling and let themselves fall on to the poor sleeping body. However the bed bug is not as crafty as this.

Bed bugs only search for blood donors when they are actually hungry. In the intervals between meals they spend their time in suitable hiding places in the vicinity of the bed. These may be crevices in the timber, joints in the bed, behind the headboard, beneath loose carpeting, behind pictures, behind wallpaper, in plug sockets, light switches, etc. When hungry, bed bugs come out from their retreat and start to search. Their senses are not capable of guiding them to a distant blood donor, but at distances of 5 - 10cm they will be attracted by the body warmth of the victim. Bed bugs can crawl up a wall and can also walk upside down on rough ceilings, but if they are not skilled they often fall down. This is the basis of stories that bed bugs, having observed that their victim had placed the legs of the bed in dishes of water, crawled up the wall and across the ceiling and let themselves fall on to the poor sleeping body. However the bed bug is not as crafty as this.